The Dynamics of Change Part One

‘My God, I feel different, I feel good’

How many of us have ached to say that with the conviction it deserves. We read up on self-help manuals, follow all the good advice and still, when the pressure comes on us, all the same old feelings and sensations return and we’re back at square one.

This certainly was my own experience when, in an effort to deal with the emotional fallout of growing up in a very dysfunctional family, I sought out help from many of the traditional routes. I tried counselling, yoga, meditation and even re-birthing, all in an effort to shift an ever present anxiety and fear, legacies of my past. But, while there was increased understanding and insight into the origins and nature of my struggle, certain areas seemed resistant to change. Hearing or witnessing violence as an adult, for example, continued to trigger the felt sense of my inner 5 year old – I again became frozen, immobile and terrified. Always accompanying the feelings was the inner dialogue ‘I’m weak and powerless. I cannot defend myself’.

Meanwhile, the capable and informed adult me became a passive bystander, unable to intercede or change anything. Somehow understanding the process didn’t seem to change it.

This was a challenge for me not only personally but also in my profession as psychotherapist, as I was coming across many clients with a similar problem. Thus I stayed hungry for any advances that addressed these difficulties. They eventually came in the form of research which arose out of an alliance between traditional verbal trauma therapy and body-oriented therapies.

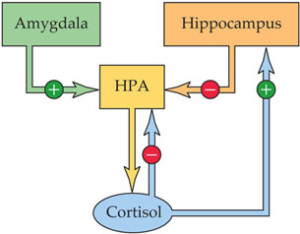

The research has, firstly, demonstrated how wonderfully primed we are to deal with a stressful situation. The mechanics of it roughly goes as follows. When your brain detects an at-risk situation, the amygdala, the brain’s fear center, signals an alarm to the hypothalamus, the main control center for the autonomic nervous system, and your Hypothalamus Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) axis is instantly activated.

A hormone called cortisol is released which primes your body for instant action – the fight/flight or freeze response. It’s saying in effect ‘Get ready everyone! This is an emergency! I want all your attention on this problem.’ When the situation is over, the cortisol is reabsorbed by cortisol receptors or dispersed and the body returns to normal. This smooth self-regulating system means we can adapt, learn and move on, free from any stressful after-effects.

Why, then, did such a smoothly operating system start to malfunction for me and countless others? The answer lies in the fact that, while some of our responses are automatic, others have to be learned. When you’re born, it’s with the expectation of having stress managed for you, as babies cannot manage their own cortisol. When we receive lots of loving touch, stroking, feeding and rocking we gradually learn the art of self regulation and cortisol levels remain low and manageable.

However, we can also be plunged into very high cortisol levels if there is no one responding to us as babies. Our natural coping mechanism then becomes overloaded and this can result in disturbing experiences remaining frozen in our brain or being “unprocessed”. Like a broken record, they can repeat themselves in our body-mind over and over again. At school, for example, I struggled to concentrate and learn as I was either being bombarded by images of drunken violence from the night before or I was living in dread of what awaited when I got home. These images and feeling could also be triggered by sights or sounds associated with the violence – a door being banged, for example.

It also matters where these traumatic memories are placed. Crucially these packages of ‘raw’ data end up being stored in the wrong form of memory.

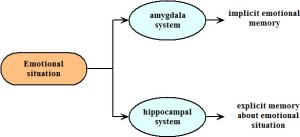

We have two different types of memory – implicit and explicit memory. When we think consciously about something and describe it with words – aloud or in our heads – we are using explicit memory. But whereas explicit memory depends on language, implicit memory bypasses it. Our memory of how to ride a bike, for example, is a form of implicit memory. It operates unconsciously and is usually not linked to explicit memory in order to help us perform such complex tasks effortlessly.

However it appears that traumatic events are more easily recorded, via the amygdala, in implicit rather than explicit memory.

Here, they can hold the feelings and body sensations that were part of the initial stressful event but, crucially, they remain isolated from the learning that results from other life experiences and so stay stuck and repetitive in our memory networks. I could say to myself ‘Patrick you’re now bigger, stronger and more able to handle violent situations. Back then you were small and deserved protection’. But, once triggered, I couldn’t feel or believe that. Instead I was back at square one terrified and believing I was somehow to blame. The implicit memory overrides the reasoning of the unconnected explicit memory every time.

This is the second of a series of articles on the subject of chronic stress.

You can read the first article in this series “The Real Enemy – Chronic Stress” here

The follow on article will focus on how we can achieve transformational change from these persistent and damaging after-effects of chronic stress.

You can read the final article in this series “A Revolutionary Approach to Healing” here

© 2016 Patrick Counseling All Rights Reserved